The fusion of robotics and artificial intelligence is accelerating, but its trajectory remains uncertain. Whether autonomy becomes a scaffold for human potential or a hollow substitute will depend on choices made in the coming decade.

Industrial revolutions rarely appear fully formed. The steam engine did not immediately replace muscle and wood; it lurked first in mines, spread to mills, and only decades later changed trade routes. Electricity began as a curiosity in lamps before it shaped how factories were built. Computers started as machines for census clerks and defence analysts, not the lifeblood of business. Robotics is tracing a similar arc, except the pace is faster, and the stakes, safety, jobs, and sovereignty, are higher.

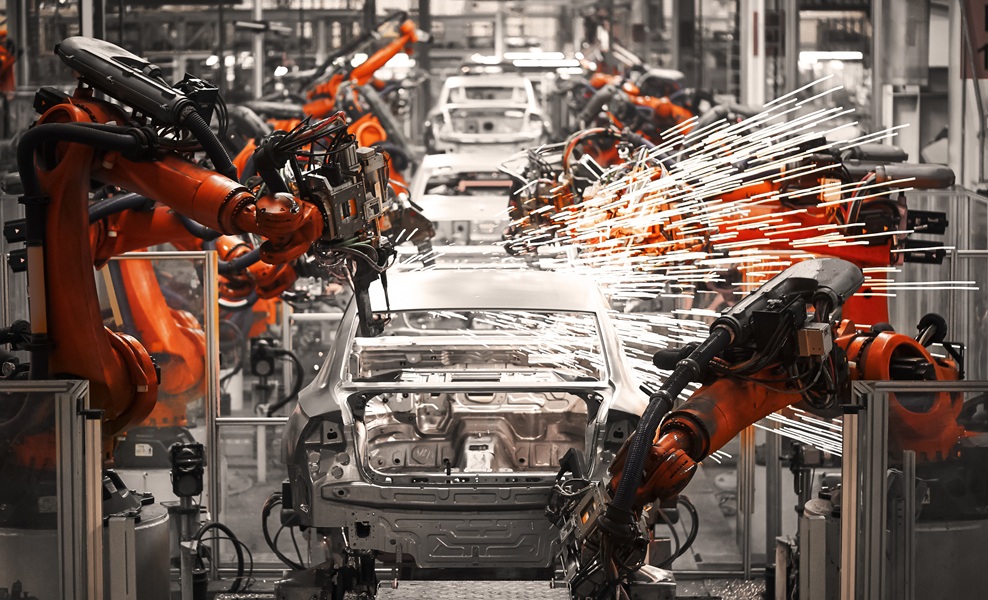

Today’s robots do not look like the tin men in science fiction. They resemble drones hovering over flare stacks, robotic arms that never tire on assembly lines, or autonomous vehicles quietly moving pallets at dawn. Their competence is fuelled by more than gears and sensors. It is driven by machine learning and AI, which allows them to see, interpret, and adapt. What was once programmed line by line is now self-adjusting. That is not a marginal gain; it changes the nature of the tool itself.

And yet, beneath the hype reels of humanoid machines or viral videos, there is a more complex question. Can industry make this shift responsibly, or will it stumble under cost, mistrust, and poor design?

Progress with friction built in

The Future of Robotics 2035 report produced by Hexagon is blunt: robots remain hemmed in by technical, economic, and social limits. Some of those limits are well known. Others lurk in the fine print. Start with dexterity. Humans can tie a knot in poor light, feel their way across pipes, or steady a fragile object instinctively. Robots still falter in environments that change unexpectedly. Glare blinds sensors. Dust clogs feedback loops. A machine that performs flawlessly in a lab may misjudge a valve offshore, and the consequences are more than inconvenient.

Money creates another brake. Global manufacturers with deep balance sheets can afford experimental automation. A mid-sized supplier cannot risk months of disruption for uncertain gain. Executives need more than promises; they need numbers, and unless the return is obvious, the cheque remains unsigned.

Culture also plays its part. A robot that unsettles staff by looking too human, or one that is introduced without explanation, can kill momentum. Resistance builds in silence, not in strategy documents. The technology might work, but the adoption fails. Faced with these barriers, the report sketches three potential futures. Total revolution is one. Stagnation is another. The most credible lies in between, the “managed mesh economy,” where robots are integrated not everywhere, but where they matter most.

By 2035, autonomy may handle half of industrial and service tasks, hazardous inspections, logistics through tangled supply chains, repetitive precision jobs where fatigue once created errors. That is not domination, but it is ubiquity in places where risk, cost, and speed collide.

This outcome depends on interoperability. Without standards, fleets remain expensive curiosities. With shared protocols, robotics shifts from flashy investment to critical infrastructure, much as electricity grids or internet backbones did. The point is not whether every workplace has a robot, but whether robots work together across sectors.

Humans remain the hinge point

Much of the debate still circles around replacement. Yet automation in history tells a different story. Office clerks adapted into analysts when typewriters gave way to spreadsheets. Customer-service staff evolved as switchboards disappeared. With robotics, the reshaping will be more profound because machines now reach both the manual and the cognitive.

The deciding principle is dignity. People do not thrive as passive supervisors of automation. They thrive when danger and drudgery are removed, freeing time for creativity and oversight. Collaborative robots, so-called co-bots, show this in practice. Workers report greater satisfaction when robots take the strain of heavy lifting or monotonous tasks while humans focus on judgment calls.

In this scenario, reskilling becomes unavoidable. The technician of tomorrow must be AI-literate. But reskilling is not enough if trust is absent. Without transparency, people will see only black boxes replacing them. Trust comes from visibility: understanding why the system acts as it does and knowing that accountability still lies with human leadership.

The spread of robotics will not be risk-free. Cybersecurity is the most obvious fault line. A compromised fleet of robots is not just a data breach; it is a physical threat. As networks of machines expand, the attack surface widens. Treating resilience as an afterthought will be catastrophic.

Ethics weigh heavily, too. If an autonomous drone collides with infrastructure, who takes responsibility? If a model trained on biased data skews decisions, who answers to regulators? These questions cannot be left to hindsight. They need frameworks as robust as the systems they govern.

And geopolitics runs through it all. Nations that dominate robotics and AI will gain significant leverage across supply chains. Those without such capacity risk dependence, and dependence in strategic industries soon becomes vulnerability.

Industry will not move at one speed

The mesh will take different shapes depending on context. Logistics is already far ahead. Warehouses hum with autonomous vehicles and drones, and the next leap is integration with generative AI that continuously optimises routes.

Automotive plants will deepen their use of collaborative robots on assembly lines, with humans shifting further into process improvement roles. Oil and gas will lean on drones and subsea robots for dangerous inspections while AI-driven twins keep assets optimised. Healthcare, pressured by ageing demographics, may bring robotic assistants into elder care and hospital logistics.

Each sector illustrates the same point: robotics does not arrive as a single event. It creeps in as a spectrum. Some uses are mature, others embryonic, and a few remain politically or ethically volatile.

The next decade will hinge less on what robots can do than on whether leaders embed them with foresight. Treat robotics as a novelty, and it will disappoint. Embed it as a structural capability, governed responsibly, connected to strategy, supported by people—and it delivers resilience.

Open ecosystems will be essential. Proprietary silos might offer control in the short term, but they will limit scale. Regulators will need to walk a fine line: encouraging innovation without leaving governance hollow. Education systems must also pivot. Preparing tomorrow’s workforce means not just technical upskilling, but cultural readiness to work with, not against, intelligent machines.

By 2035, the choice will be clear

Robots are unlikely to dominate every space by 2035, but they will underpin critical infrastructures as naturally as power and data networks do now. They will not be curiosities wheeled out for trade fairs but unseen scaffolding, stitched into the fabric of industry.

The question is not presence but purpose. Do they amplify human judgement, or reduce work to a mechanised routine? Do they spread prosperity, or concentrate it? Do they make systems resilient or brittle?

These are not matters of engineering alone. They are questions of leadership and culture. The managed mesh scenario is persuasive because it recognises nuance. It avoids utopia and dystopia alike.

If autonomy is built with transparency, accountability, and human dignity, it will act as a scaffold for industry. If not, it risks becoming a hollow substitute that fractures rather than fortifies. The decisions taken between now and 2035 will determine the world we inherit.